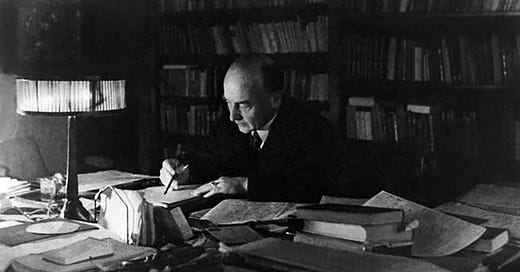

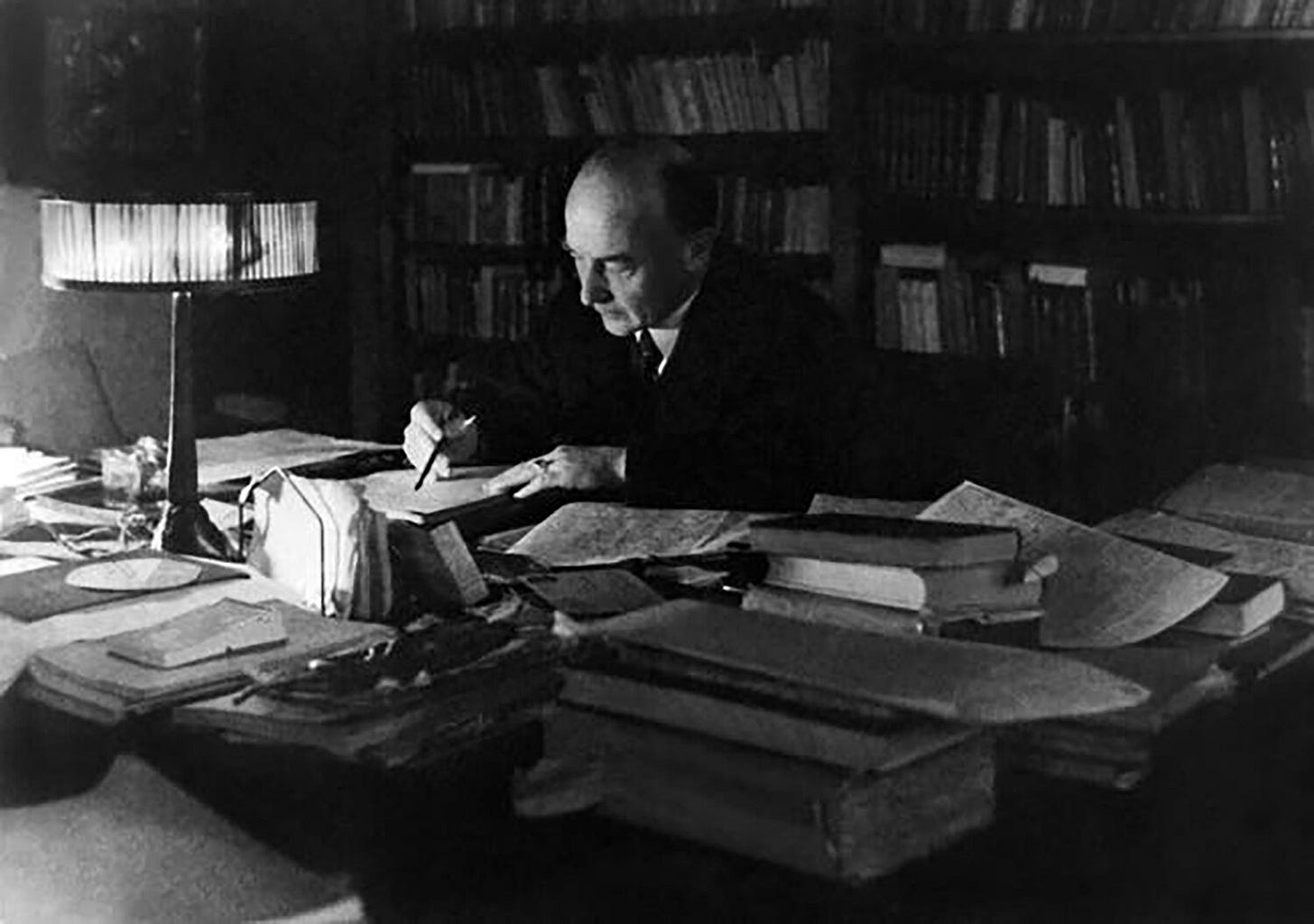

In 1932, Musil asked Wolfdietrich Rasch what he thought about the reception of his books. Rasch recalls that they “were sitting in his Berlin Pension room at his work desk. A bright, sharply-edged circle of light shone from his shaded desk lamp, cut out of the shadowed darkness of the desk’s surface, which was covered by manuscripts and galley proofs of volume two of his novel” He “answered Musil that one could demonstrate by the illumination of this lamp the way his novel had been received: very intensely by a limited circle of cognoscenti and sophisticated, discerning readers—and outside of this circle, by basically no one at all.”

Musil answered: “Yes, there are no bridges; there seem to be only admirers and indifferent people…” (From En Face, p.221).

When one sees the glowing reviews and reads the admiring praise heaped upon Musil during his lifetime by this small circle, one may not, at first, be able to reconcile his constant gripe that “nobody thinks of me” in response to the relatively greater attention given to many other authors—many underserving—by the press, the purveryors of awards, the book-buying public. The bridges were indeed few between the circle of admirers and all the rest of the general readers: Törleß had been a real success, selling out multiple printings and bringing him great initial acclaim. His farce, “Vinzenz and the Mistress of Important Men,” had had a limited, short, popular acclaim. A number of awards were given to him, and he was nominated for many. One of his stories, “Flypaper,” was, as Corino writes in his Biography, a sort of “milk goat or honey bee, that periodically churns out its little pot, but naturally was not able to feed him.”

Part of the problem was the challenging nature of much of his writing: the philosophical and scientific content and his tendency to push against the boundaries of traditional morality and readerly expectations. The two stories published as Unions after his initial success with Törleß certainly asked a great deal of the reader. He was certainly never going to be the kind of writer he contemptuously dubbed a “Großschriftsteller” (bigshot writer), but he did not aim to be obscure. Yet the length alone of his great novel-in-progress not only discouraged some readers but simply and practically meant that the time needed to write its continuation often outran the advances given by even the most generous publishers.

Speaking of these generous publishers and the small, intense circle of light, there is a wonderful story about how much Rowohlt appreciated Musil. In 1931, when the publishing house was in debt and a financial overseer from the Ullstein firm was called in to look over the accounts and reorganize the business, Rowohlt was asked why in the world did they keep paying this Musil advances when even the chief editor, Paul Mayer, had admitted that neither he nor Rowohlt expected financial success from the publication of Musil’s works. Mayer answered that inasmuch as the material success of the book was unpromising [or hopeless], the literary value of the book was beyond all question. Mayer explained: “For the Rowohlt Publishing House, The Man Without Qualities is a matter of life and death!” Referring then to the illustrous German publisher, Cotta, he continued, “The Cotta Publishing House had their Goethe and we have our Musil” (Reported in Walter Kiaulehn’s Biography of Rowohlt and quoted in Briefe II, p.307). Did Musil know about this conversation? Unfortunately, I think not—it would certainly have cheered him.

With the rise of the Nazis on the one hand and the Stalinists on the other, Musil’s work became even less popular among the masses. He was unwilling to cheer along with those who saw the Soviet experiment as a utopian salvation (“Down with cultural optimism!” he wrote in a note related to his appearance at the Communist-organized Paris Conference for Writers Against Fascism in 1935), and even less willing to march in goosestep with the Nazis. Though he was nominated for the Goethe Prize of Frankfurt in 1933 and the Harry Kreisman Foundation Prize in 1934, he was overlooked in favor of more “German-friendly writers”. Once he left Germany in 1933 and then Austria in 1938, following the Anschluss, the Reich declared The Man Without Qualities as “undesirable literature” and the novel and Posthumous Papers of a Living Author were both banned in Germany. The majority of his readers and supporters (the heart and purse of the organizations founded to help him financially) were Jewish and had to flee the Reich if they were able, and if this was not possible, they were in worse trouble than he and Martha (who were in relative safety in exile in Switzerland).

In Switzerland—particularly in French Geneva—he was practically unknown, was not (he complained) invited to readings or cultural events, nor spoken of in the press, and was forced to beg for whatever monies could be squeezed out of the aid organizations in America, France, and in Switzerland (see other posts on exile in Switzerland for some of the reasons the Musils were particularly hard to help). While others, like Thomas Mann or Hermann Broch were celebrated and comfortable in the United States (Mann was living like a royal in California and Broch, who had been helped by James Joyce and others to emigrate, was well-funded and thriving in Princeton, New Jersey), Musil was unable to get more than a few pieces translated (into French and English) and had neither the funds nor the help to emigrate or live more than a hand-to-mouth existence of anxiety clouded by a sense of being forgotten.

While today he is considered the greatest or one of the three greatest writers of 20th-century German prose (depending on which poll, etc.), in America his work is still only illuminated by that small circle of light cut out of a wider dark surface. May my work help to build some bridges to the outer shadowing realm, extending the circle wider and wider. You can help, too.