Excerpts from Burton Pike's Musil Notes

"...looking for a place the individual can fit in in a deadened, shallow world."

[In a recent post I mentioned that Burton Pike had gifted me his notes on Musil at a time when he thought he wouldn’t write about him anymore. It is a precious horde of insights that reveals something of what Musil meant for Burton and also something of what literature meant for him: always something deeply connected with human life, never something dry or academic. Enjoy!]

p. 169: Quote from William James (Principles of Psychology 2:284):

"'The true opposites of belief, psychologically considered, are doubt and inquiry, not disbelief . . . . Both sorts of emotion may be psychologically exalted . . . . The pathological state opposed to this solidarity and deepening [of belief] has been called the questioning mania (Grübelsucht by the Germans). It is sometimes found as a substantive affection, paroxysmal or chronic, and consists in the inability to rest in any conception, and the need of having it confirmed and explained. "Why do I stand here where I stand?" "Why is a glass a glass, a chair a chair?"'"

---------------------------------------------------

Herbert Spiegelberg, The Phenomenological Movement: A Historical Introduction, 2nd ed. (The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff, 1971). GC: B 829.5 .S6423

(contains valuable summaries of Brentano, Stumpf, Heidegger, Hartmann, etc.)

Vol. I, part 3, chapter 3: [Husserl's] Ideal of Rigorous Science

p. 80: " . . . the incapacity and unwillingness of science to face problems of value and meaning because of its confinement to mere positive facts seemed to [Husserl] to be at the very root of the crisis of science and of mankind itself. In contrast to the science of the Renaissance, which had been part of a comprehensive philosophical scheme, a positive science of mere facts appeared as a truncated science endangering man, and in fact endangering itself, by a 'decapitation.'"

-----------------------------------------------------

A late poem by Rilke, for comparison with Musil's Torless

Herbst

O hoher Baum des Schauns, der sich entlaubt:

nun heißts gewachsen sein dem Übermaße

von Himmel, das durch seine Äste bricht.

Erfüllt vom Sommer, schien er tief und dicht,

uns beinah denkend, ein vertrautes Haupt.

Nun wird sein ganzes Innere zur Straße

des Himmels. Und der Himmel kennt uns nicht.

Ein Äußerstes: daß wir wie Vogelflug

uns werfen durch das neue Aufgetane,

das uns verleugnet mit dem Recht des Raums,

der nur mit Welten umgeht. Unsres Saums

Wellen-Gefühle suchen nach Bezug

und trösten sich im Offenen als Fahne **

.........................................

Aber ein Heimweh meint das Haupt des Baums.

Autumn

O high tree of looking, which is dropping its leaves:

the task now is to be equal to the excess

of sky that breaks through its branches.

Filled by summer, it seemed low and dense,

almost thinking us, a familiar head.

Now its whole interior becomes a road

of the sky. And the sky does not know us.

Something most extreme: that we throw ourselves

like birds in flight through the newly opened up,

which denies us with the right of space

that only consorts with universes. The

wave-feelings of our edges search for connection

and comfort themselves as banner in the openness--

……………………………………..

But the head of the tree thinks: a homesickness.

------------------------------------------------------

Richard Ohmann, "The Shaping of a Canon: U.S. Fiction, 1960-1975", in Critical Inquiry 10:1, 1983, 199-223

213: [taken out of context:] "one cannot . . .cease to be social: at a minimum, social roles are indivisible from selfhood. . . .The ideal calls for a self that is complete, integral, unique, but in actual living one must be something and somebody, and definitions of "somebody" already exist in a complete array provided by that very social and economic system that one has wished to transcend. Society comes back at the individual as a hostile force, threatening to diminish or annihilate one's "real" self. Furthermore, society has the power to label one as sick, if one is unable to make the transition into a suitable combination of adult roles."

------------------------------------------------------------

From Translating Freud, ed. Darius Gray Ornston, Jr., M.D. (New Haven: Yale UP, 1992), 20:

"Scientists use mathematical language in three ways: to make an initial observation, to measure an apparent difference, and to construct a statistical proof."

-------------------------------------------------------------

From George Steiner, After Babel: Aspects of Language and Translation (London: Oxford UP, 1975),

103: "…it is its great untidiness that makes human speech innovative and expressive of personal intent. It is the anomaly, as it feeds back into the general theory of usage, the ambiguity, as it enriches and complicates the general standard of definition, which give coherence to the system. A coherence, is such a description is allowed, 'in constant motion'. The vital constancy of that motion accounts for both the epistemological and psychological failure of the project of a 'universal character.'

"Roughly stated, the epistemological obstacle is this: there could only be a 'real' and 'universal character' if the relation between words and the world was one of complete inclusion and unambiguous correspondence. To construct a formal universal syntax, we would need an agreed 'world-catalogue' or inventory of all fundamental particulars, and we would have had to establish the essential, uniquely-defining connection between the symbol and the thing symbolized."

204: "Natural language is local, mobile, and pluralistic in relation to even the simplest acts of reference. Without this 'multivalence' there would be no history of feeling, no individuation of perception and response."

234: "Man has 'spoken himself free' of total organic constraint. Language is a constant creation of alternative worlds. There are no limits to the shaping power of words, proclaims the poet. 'Look,' says Khlebnikov, . . .in his 'Decrees to the Planet', 'the sun obeys my syntax'."

-----------------------------------------------------

Henry James on Turgenev:

“The thing [story in Turgenev’s fiction] consists of the motion of a group of selected creatures, which are not the result of a preconceived action, but a consequence of the qualities of the actors. Works of art are produced from every possible point of view, and stories, and very good ones, will continue to be written in which the evolution is that of a dance—a series of steps, the more complicated and lively the better, of course, determined from without and forming a figure. This figure will always, probably, find favor with many readers, because it reminds them enough, without reminding them too much, of life.”

Partial Portraits (New York: Macmillan & Co., 1888)

------------------------------------------------------

For MoE: Where does Hegel talk about "the fan of possibilities as a metaphor for freedom"? Check Tb

What M. is always about, why he haunts: looking for a place the individual can fit in in a deadened, shallow world. This is more important than his ideas, which are (in the essays) hortatory and not new, or indeed constructive, but hortatory to change; cf. Rilke, the goal of art is to produce in reader a moral imperative to change his life. This is more important than his ideas, which are (in the essays) hortatory and not new, or indeed constructive, but hortatory to change; cf. Rilke, the goal of art is to produce in reader a moral imperative to change his life.

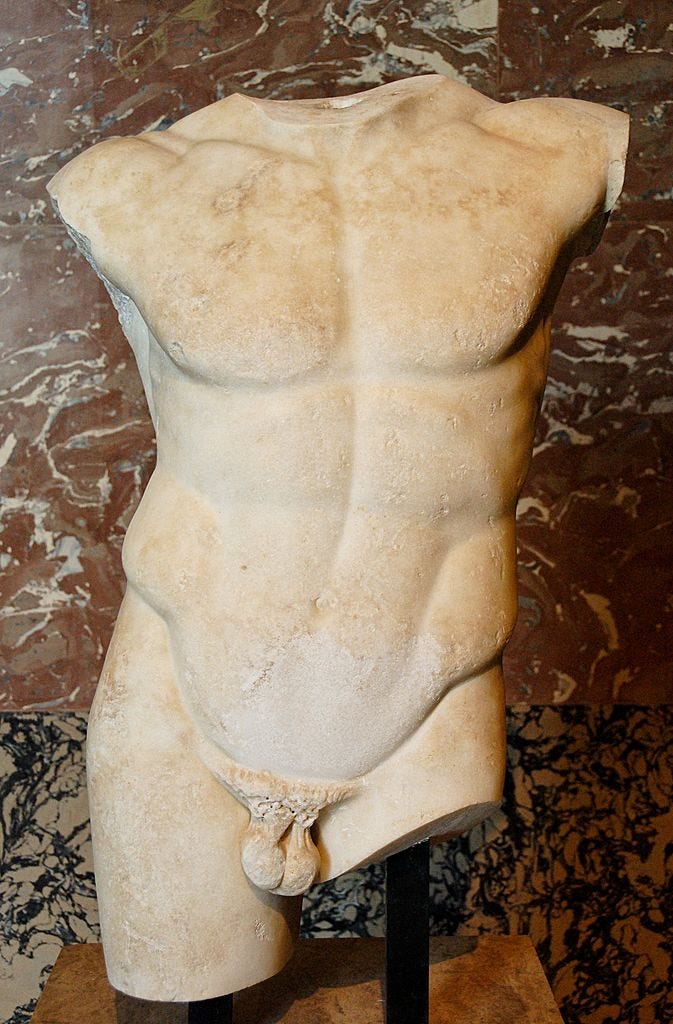

Image of the Diadumenus at the Louvre is made available by Wikimedia under a Creative Commons Attribution ShareAlike License.