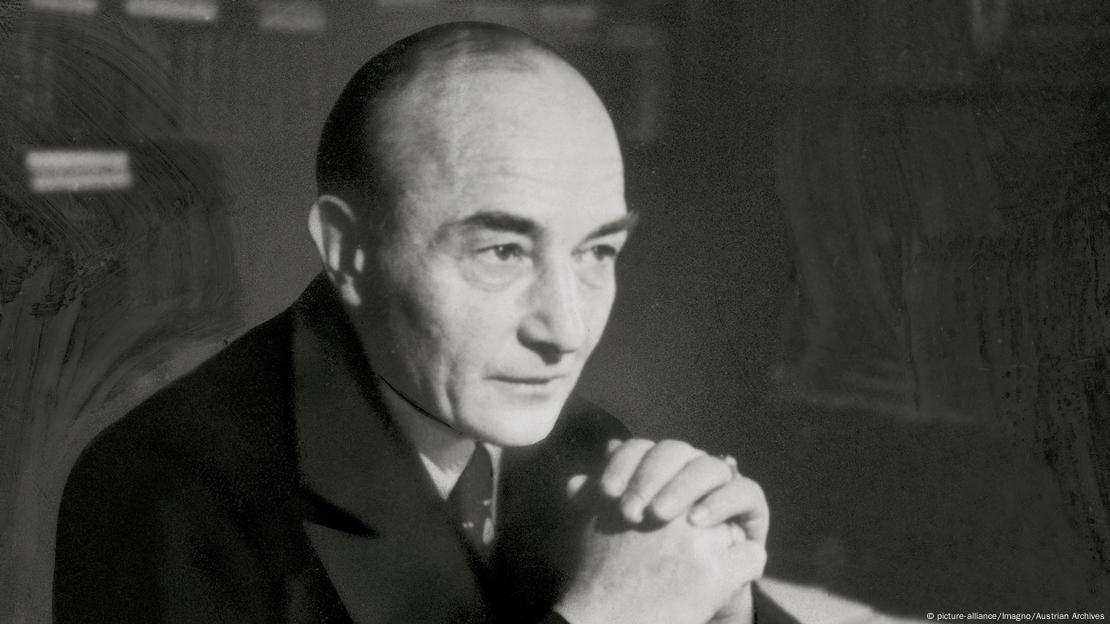

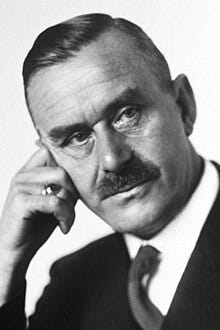

I promised an analysis of the complex relationship between Thomas Mann and Robert Musil a few weeks ago—and I have been working on it. But it has gotten so out of control that it has become a whole chapter in the book, so I thought I would just casually summarize, here, some of the main issues that came up in my research and deeper thinking about these two writers.

It’s true that Musil’s judgments on Mann were tainted by his rancour at the “Great Man of Letter’s” success and his own relative neglect. Not only was Mann extremely successful and extremely wealthy compared to Musil, but he posed as a self-appointed intellectual prince representing German literature—an assumption that rankled and repulsed Musil for a number of relatable reasons. In one extreme moment, Musil actually compares Thomas and Heinrich Mann to Hitler—because they all three strove to be intellectual and spiritual leaders of the nation. Musil notes that he would not ever do something like that, would not set himself up as the spokesman, the arbiter of good or evil, for to do that would be a form of bewitchment, dishonest.

Musil’s reluctance to be a spiritual or intellectual guide for the nation is related to another of his repeated criticisms of Mann as artist: that he smooths over complex problems and intellectual conundrums far too glibly. He gives his readers and himself a sense that all is right with the world—albeit while slyly winking at them about certain minor perversities and artistic bohemianisms. Musil, as defender of all exceptions to the rules, finds that Mann’s leveling of the exceptions into the norm is a great fault.

Further, Musil contends that Mann only uses intellectual content as filler, without really caring to grapple with philosophical problems. Shortly after Musil himself was deemed “too intelligent to be a creative writer,” he wrote to his friend Allesch that the intellectual parts in Mann’s Magic Mountain were like the inside of a “shark’s belly”—that they “completely failed.”

This may also be related to their divergent ideas about the value of ideas in fiction. Musil read Mann’s 1918 book Reflections of a Non-Political Man in 1919 and noted—despite reservations about Mann’s German nationalism and attack on democracy—many ideas in it with agreement (that the cataclysm of the war was wanted, needed; that art must be protected from the encroachments of politics; that as an artist one is de facto revolutionary, but to be revolutionary in politics is a mistake), but Musil disagreed sharply with Mann’s favoring of feeling over thought.

Musil also is disturbed by the way Mann can praise both a great writer (like Musil himself) and a mediocre one. And he notes that this ability is part of what makes Mann so popular—as the public, too, does not make distinctions.

The character Arnheim in The Man Without Qualities was at first based largely on Walther Rathenau, statesman and “universal man.” But after his assasination in 1922, this character came to take on more of Thomas Mann’s characteristics—thus the “Great Man of Letters” chapters in volume II of the novel are definitely portraits of Mann himself.

Their relationship was outwardly friendly, with exchanges of inscribed copies of their books and birthday tributes; and Mann helped Musil repeatedly, with gushing reviews and references, and, after the Anschluss, with plans for possible emigration, and in securing aid from organizations. Sometimes this aid was not enought to ensure that the Musils could live more than an anxious hand-to-mouth existence and sometimes it may have seemed that Mann was neglecting Musil or not doing his utmost to help him. But, as mentioned in other posts, Musil was not always easy to help. Though Musil continued even in exile to confide his disgruntlement with Mann to his diaries and sometimes criticized his work in letters to friends, he also acknowledged his own possible responsibility for the fact that he was isolated and neglected—his temperament, his coldness, his untimeliness—and admitted over and over that he had been unfair to Mann out of envy. At one point, after complaining that his friend Olden had written about Thomas and Heinrich Mann in the same breath as Goethe, Kleist, and Schopenhauer (but had not mentioned Musil), he even calls himself a “poisonous scoundrel” for his “paroxysm about the plurality of Manns,” and notes that he would have done better to have expressed his esteem for the Great Man of Letters, rather than his chagrin.

More soon, on this and other subjects….

At the time I think the Helen Lowe-Porter was the only English translation. I think he favored its elegantly engaging style and perhaps more humanizing feminine touch to the original, which he may have remembered as too stuffy at times. Just a guess.

There's a passage in MWQ where Ulrich dreams of attempting to climb a steep mountain and failing. I take it to mean The Magic Mountain and Musil's desire to take it measure.

A German-speaking friend said he preferred the Lowe-Porter translation -- "Less pompous!"