Musil's Mother, Hermine

"My mother was oddly confused. Like slept-on hair over a pretty face.”

Happy Mothers’ Day to all of you who are or have mothers. Musil’s relationship with his was stormy, complicated, deep, and difficult.

Below you will find some excerpts from the biography draft about Hermine Musil, neé Bergauer.

Hermine: there she sits at an elaborately carved escritoire, its feet in the shape of oriental dragons. She is perched upon a velvet chair with a large pendant tassel. Her dress is outfitted with a bustle projecting back from her corseted waist, and its skirts cascade down to the floor with layer upon layer of ruffles and lace. Half turned, looking provocatively at the camera beneath piles of wild dark hair that erupt volcanically from atop a disorderly coiffure, she reveals a fiercely sensual quasi-madness. Her broad forehead is festooned with the ringlets and the bangs that were then stylish, and there are soft curls surrounding her long, fleshy face. Her dark eyes and eyebrows are strikingly like those of the son who will be born to her in 6 years, and also like those of her mother, Emmeline Bergauer. Robert will inherit his grandma Emmeline’s mouth and chin, too. But he will look especially like his mother in a portrait at 7 years old, in a sailor suit posed upon studio rocks. One leg across the other, he gazes out, challengingly, like her; he is skeptical, keeping his own counsel. There seems to be no physical resemblance whatsoever between Robert and his father.

Hermine and Alfred make an odd couple; one imagines she might smother him, overwhelm him, confuse this compact, self-contained man. Indeed, in a sketch titled “The Mother,” from 1918, written when Alfred was ill and “Minerl”—as her husband affectionately called her—was caring for him, Robert wrote: “She mistreats her husband, neglects him. But jealously caters to his wellbeing. He, conscience-stricken a[nd] grateful. The Minerl, who does everything for him. He is the prisoner of her need for power in the arena of Goodness.” Could any of this have been predicted by the two contrasting pre-nuptial photographs? What did Alfred’s elder brother Rudolf think when he was given a copy of Hermine’s portrait, with the words, “My darling fiancée, Hermine,” written upon it?

[…]

While the furnishings in the portrait of Hermine probably belonged to the photography studio, they may nevertheless tell us something about the style in which she wished to be represented: properly Biedermeier, but with a sumptuous and romantic twist. Was Hermine responsible for the decoration of the newlywed’s Klagenfurt lodgings or did Alfred (who painted realistic portraits and also rather surprisingly silly mythological landscapes with winged cupids and floating swans)[i] have a say? Along with the piano, she must have come with valises filled with frippery—indeed, an early childhood memory of Robert’s involves “momma’s trunks,” with their erotically fragrant furs.[ii] And from what we know of her life-long interest in literature and culture, she must have brought books, including, for certain, “a reference library, which did not fully neglect the contemporary,” while, “according to the judgment of their son—her husband’s book collection did.”[iii] Robert’s childhood friend, Gustl Donath (model for Walter in The Man Without Qualities), who knew the family intimately from their Brno days on, tells us that Hermine was “very sensitive, a good pianist… always anxious to take an interest in art and everything worth knowing and also to initiate her son therein.”

What was their early domestic life like?

Any new wife, suddenly separated from her family and friends and settled in a new city with her husband, may feel lonely, anxious, unsatisfied. Her husband was certainly a workaholic, but she would have been familiar with the particular milieu of engineering and invention from her family home. Although she was the youngest, and her brothers and sister had all either moved away or died by the time she was married, one gets the idea that the Bergauer household she had left behind was still quite warm and lively.

[…]

In any case, it was clearly a household where people dropped in, sat about gossiping in the parlor, laughing at the follies of everyone who was not part of the extended family circle. Hermine’s life in a new city, mistress of her own parlor—albeit only 25 miles from her family home in Linz—would have been quite a change, possibly liberatory, but possibly also disappointing and lonesome.

How soon did Hermine or Alfred become aware of the “particular tragedy of their marriage?”[i] Robert writes in retrospect, “She esteemed my father, but he did not suit her proclivities, which appeared to tend toward a manlier man. Later, hysterical traits…or rather a nervous inability to come to terms with something that led to a convulsive reaction.”[ii] Was this something she could not come to terms with perhaps her marriage to a man whom she did not desire or who was not sufficiently passionate to fulfil her own expectations?

[…]

While the Family Musil would only end up staying in Robert’s second home for about a year, the acquaintance made there with Heinrich Reiter, who worked under Alfred as a teacher at the school he directed, would be life-changing. Reiter, born in 1856 in Grieskirchen, Upper Austria, was ten years younger than Alfred and three years younger than Hermine and was surely a model for a certain “Hyazinth” who appears in Robert’s novella “Tonka” as, “a friend of both parents…one of those uncles, whom children just find there, when they open their eyes.” Technically, unless there is something all researchers have missed, the Musils met Reiter when Robert was already about one year old, and there would have been no foundation for the fantasy, aired by Robert in at least one draft sketch, “Story of Three People,” that Heinrich—who in this version of reality was a writer—was his real biological father (“Perhaps,” Robert wrote of himself in the third person, “he had inherited his literary talent from him”).

It is unclear how much contact the Musils had with their “friend” Heinrich in the 6 years after 1882, when they moved to Steyr and he to Bielitz, nor is it out of the question that one impetus for their move to Steyr was to separate Hermine and Heinrich.[i] Considering also that Alfred was Heinrich’s professional superior, could it not have been possible that he had his rival transferred as far away as possible? Bielitz, once a Silesian outpost of the Empire, is now Bielesko, Poland—an extreme Eastern location. Even if any of this were true, the stratagems did not work and by 1888, when the Musils had already been living in Steyr for six years, they went on a trip with Heinrich to the Tirolian resort destination of Achensee, approximately 510 miles from Heinrich’s home and about 300 from the Musils’. Heinrich could have picked the Musils up on his way and shared a railroad compartment, liverwurst sandwiches, and thermoses of coffee with them.[ii]

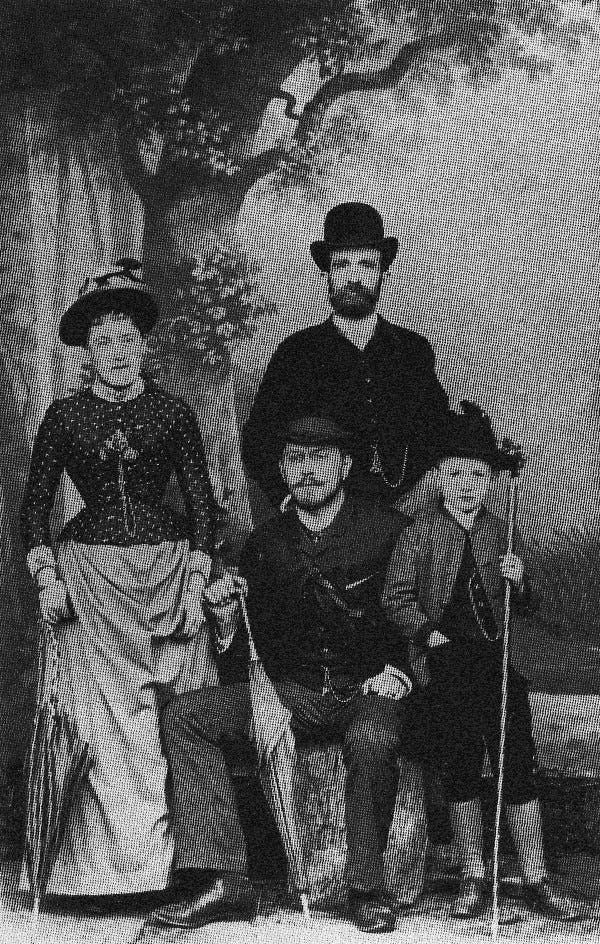

The pleasure trip is memorialized by a photograph that seems to many commentators to speak a thousand words about the unusual family dynamic. The picture is certainly revelatory: Reiter seems to fill up the picture frame with his broad shoulders, taking his place, as if as a matter of course, in the center of the family constellation. His feet are firmly planted, with one knee spread wide to touch Hermine’s skirts; his hand, holding an umbrella, is possibly grazing hers. Heinrich is the only one seated of the quartet, and the artificial boulder that serves as his throne rises up behind him and Robert, seeming to separate Alfred decisively from the trio. Alfred almost seems like a spirit from another world, benevolently watching over the others from an immeasurable distance, in a black jacket and bowler hat, his large ears sticking out awkwardly. Hermine, in what looks to be a bonnet decorated with leaves or flowers, wears a corseted and corsaged jacket over floor-length skirts. Like Reiter, she holds an umbrella—a parasol really—and her coiffure is a great deal tamer than that in the portrait taken almost ten years before. She stands to Reiter’s left, looking out dreamily, perhaps with a touch of bitterness, into the distance, and Robert stands to the “house friend’s” right. While the boy, clothed in a natty Tyrolian hat, vest, and jacket, leans slightly toward Heinrich, possibly at the command of the photographer (move a little closer!), his one hand is carefully separated from the intruder: he has stuffed it defiantly into the pocket of his knickers, while with his other hand he seems to stab the ground with his Alpine walking stick.

[i] No one, as far as I know, has suggested this, but I deem it worth considering that the usual description of a completely passive cuckolded husband may not be absolutely correct.

[ii] Consider the erotics of the train compartment, illustrated with painstaking detail in Robert’s story about adultery, “The Completion of Love”.

[i] Dinklage.

[ii] T 935.

[i] It is unclear when this hobby started.

[ii] Seee also mention of this trunk in the small prose piece, PA and the Dancer and his play fragment, Horoscope/ ThoughtFlights and Theater Symptoms.

[iii] C’s Von der Seel, 299.

Musil is fortunate to have such a wonderful writer and thinker as a biographer!