In my last post I wrote a bit about how Musil helped other writers in the years between WWI and WWII. Throughout the twenties and thirties, he continued to work to connect writers with publishers and magazines, wrote reviews, answered annual questionnaires about his favorite books of the year, and even took the time to give some young writers and painters advice. Many of these writers’ names will be unfamiliar to American readers, but perhaps Musil’s praise of them could inspire someone to translate and publish some of these works.

While some of the praise—private responses to the authors who sent him their books or even public laudations of friends and colleagues for the purpose of keeping up the mutual admiration society—may be exagerrated, at other times we have private notes that show his true evaluations.

He thanked and praised Andreas Thom for his 1930 novel, Vorlenz, der Urlauber auf Lebenszeit, und Brigitte, die Frau mit dem schweren Herzen (Vorlenz, the vacationer for life, and Brigitte, the woman with the heavy heart) and his 1936 Das Sylvesterkind (the new year’s child); praised the works of Otto Wirz in 1933, helped Oskar Maurus Fontana get his 1929 book, Gefangene der Erde (Captives of the Earth) published and praised Fontana’s book, Der Sommer Singt sein Lied (the summer sings its song). He praised and thanked Walther Petry for sending him his poems and expressed good expectations for Petry’s novel-in-progress. In 1930 he praised and partially critiqued Béla Balažs’ Unmögliche Menschen (impossible people), demonstrating that even in a personal letter he could be honest about his assessment. He praised a book of 1935 essays, Von Gott und der Welt (on God and the world) by Richard Moering: “for the wit and the intellectual preeminence with which this book is written, constitute a delicious rarity among contemporary writers.” He thanked and praised Siegfried Krakauer and Soma Morgenstern for their gifts of books, and recommended Italo Sveno’s Cosini (translated from the Italian, La consienza di Zeno, into German by Piero Rismondo) and a translation of Jules Romain’s Hommes de bone volonté (men of good will).

In 1924, his choices for remarkable books of the year were: Sprung auf der Strasse (leap onto the street)—a book of poetry by Victor Wittner; Die Insel Elephantine (the Elephantine Island)—stories by Oskar Maurus Fontana, Egon Erwin Kisch’s collection of feuilletons, Der Rasende Reporter (the raging reporter), a book of essays called Das Kuriositäten-Kabinett der Literatur (the curiosity cabinet of literature) by Franz Blei, and Der Fall Elli Link (the case of Elli Link) by Alfred Döblin, and Der sichtbare Mensch, oder die Kultur des Films (The Visible Man or the Culture of Film—which has been translated into English), by Béla Balažs.

In 1928, when asked in a survey what book made the greatest impression on him in 1928, he answered William Beebe’s Das Arcturus-Abenteuer. Tiefsee-Expedition der New-Yorker Zoologischen Gesellschaft, a German translation of The Arcturus Adventure: An Account of the New York Zoological Society’s First Oceanographic Expedition.

In 1930, his list of the three best books was, 1. Döblin’s Berlin Alexanderplatz, 2. Oskar Loerke’s poems, Atem der Erde (breath of the earth), 3. Ernst von Salomon’s book about the young nationalists who assassinated Walther Rathenau, Die Geächteten (translated into English as The Outlaws). There was then a special mention of two books by Franz Blei: Formen der Liebe (forms of love) and Erzählung eines Lebens (narrative of a life) and Ernest Hemingway’s In einem Anderen Land (A Farewell to Arms) in a German translation by Annemarie Horschitz. In his notebook, he wrote that Die Geächteten “surprised one by the talent of its author and grasps the reader in the most lively way. For his young people, who are outcast by almost all of Germany, emit a powerful melodic energy—an energy lacking only the right conviction.”

To keep this last book in the public eye a little longer, Musil included a few small errors in his review, which then had to be corrected in the following week’s paper.

In 1935, his pick as best book for “Flink’s Survey” was Rudolf Carnap’s Logische Syntax der Sprache (Logical Syntax of Language).

Despite all of this activity of praise and promotion for his contemporaries, when asked in 1936 by Béla Köhalmi, the director of the Budapest State Library and editor of the newspaper, Magyar Könyvszemle, about his experiences with reading—especially about which books he felt were “trouvailles,” or “lucky finds” or “windfalls,” Musil answered:

“Indeed, I would be able to name a few books of literature that have appeared in the last twenty years that I deem far better than average, yes, that are eminent or that I have admired for their technique, but to tell the truth, I would have to reflect for quite a while. . . It is thus obvious that I cannot respond to your criterion of the “trouvaille,” if by that term I am right to understand a passionate love for a new book, at first sight, so to speak.”

“The blame may be my own, or may be down to the others, or to other accompanying circumstances. I would not like to conceal that, during the same time, I have felt the pleasure you ask about when reading older books. I have reread Tolstoy with admiration, though he meant little to me in younger years. (Dostoevsky, on the other hand, was a star over my youth, and it is difficult for me to read him now); I have felt ecstatic reading Lichtenberg; and—as unseemly as it may be to discover Goethe, this has happened to me. I am not sure whether I should consider this a meaningless personal matter or a general contemporary experience.”

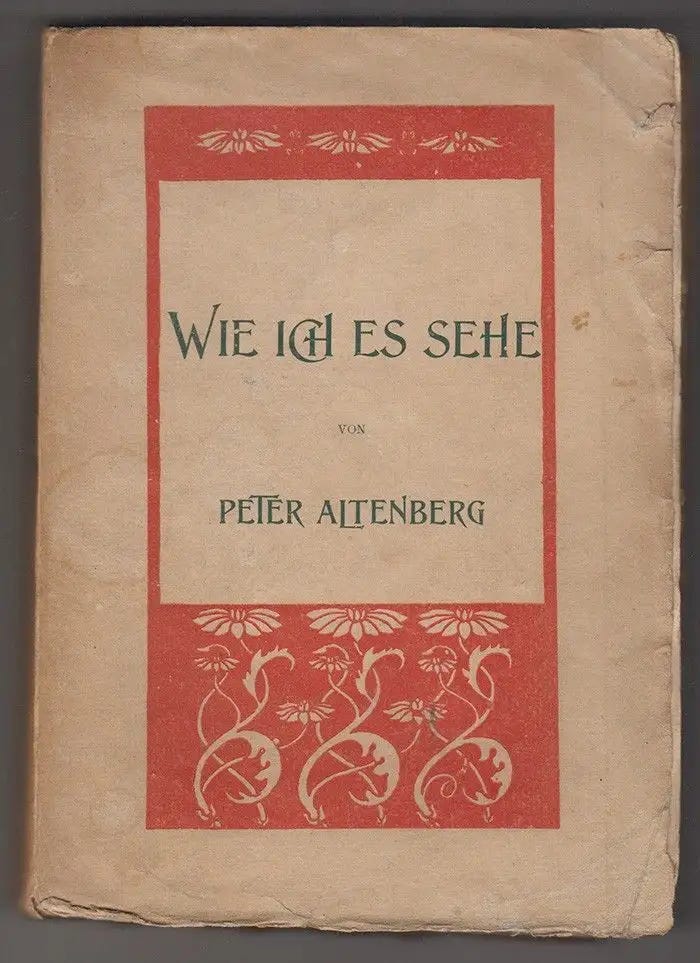

In 1938, in an answer to a question from Roy Temple House, published in an article titled, “My Debt to Books/A Group of Writers’ Confessions” in the Spring edition of Books Abroad, in the U.S., he wrote that “from my fifth to my seventeenth year I wrote with more conviction than ever since then, but I am not able to call up what inspired me to be a writer at that time. From my seventeenth to my twentieth year, it was more the literary atmosphere of the time of the “Modern” in Germany that emboldened me than any particular books; at that time I also developed the formation of my style and my views more from the sciences than from belles lettres. Nevertheless, I would like to name a few books from the realm of literature which I abused in my youth in order to find myself, i.e., the following: Maeterlinck, Wisdom and Fate; Emerson, Intentions [unclear which book Musil means by this title, though he certainly was steeped in Emerson’s Essays at this time] ; Nietzsche, Jenseits von Gut und Böse [Beyond Good and Evil] and Genealogie der Moral [Genealogy of Morals]; Novalis, a selection from his aphorisms; D'Annunzio, Pleasure; Jacobsen, Niels Lyhne and Maria Grubbe; Dostojewski, Raskolnikov [Crime and Punishement]; Tolstoy, Resurrection. I must add that Pleasure, no matter how much beauty it contains, influenced me more through its errors; and must also add Altenberg, Wie ich es sehe [How I see it], and perhaps a few of Schnitzler’s earlier works.

Over and over in his notes, we read that Musil’s three most important influences were Nietzsche, Emerson, and Dostoevsky, and though in 1938 he write that he could not read Dostoevsky at that time, he delved deeply into him again in the last year of his life. His favorite poet (despite occasional ambivalence) was Rilke. I already mentioned Musil’s beautiful review praising Kafka and Robert Walser from 1914. A whole other post will have to deal with Musil’s complex relationship with Thomas Mann.