Strange Patriots

Where there is much light, there is much shadow.

A man was sent out from the trenches. He was supposed to feel out what patriotism was. Not the patriotism that one knows because one practices it every day without words, but rather the great new Austrian patriotism, about which one has heard so much talk. Our man found, in fact, patriotism of many kinds.

So, he found, along with tongue patriotism, lung patriotism.

The tongue patriotism he knew about already. He had enjoyed saying: Really, Austria is the richest land in the world; really, Austria is the land with the greatest talents of the world; really, Austria is the best-situated country in the world; really, Austria is the happiest country in the world. This “really” was, however, cracked from a rotten egg, from the same one that dreaminess and melancholy come from.

The war changed this fundamentally. Now it went: And we were indeed “we”. How great, how united, how organized we are, we had not known this. They couldn’t even starve us to death, despite the fact that we are naturally one of the richest lands, we didn’t know that. Just look, how filled with enterprising strength we are, we did not know that. Nowadays, the Austrian seems to be proud of nothing as much as of the fact that there was something he had not known about. — In response to the objection that this is hardly a reason to be especially hopeful about the future, since at bottom all the tribes of fragmented Russia are united, since even France, allegedly so morally vitiated, is powerful, since overall everyone has energy in the final moment and that therefore any superiority lies in having it beforehand, in preparedness, in having a head start, and in whatever now would happen as a result of it, in response to this objection, one can answer: the trenches!

The trenches filled all minds with something mysterious and shining. The democrats said: the people in the trenches learned self-sufficiency; when they come back you’ll see right away. The autocrats said: learned to listen, you’ll soon see. The clerics said: learned to pray, you’ll soon see. The free spirits said: learned to trust themselves, you’ll soon see. The friends of the nation said: learned to appreciate a strong regiment, you’ll soon see. The politicians said: won’t let themselves be patronized, you’ll soon see. And everyone says: them? You’ll soon see. Everyone waits with a childish trust for what the others will certainly do when they come out of the trenches. The trenches were the mirror in which everyone saw his own image; the trenches were the fairy tale uncle from America, who would bring everyone the big money. The trenches were Schlaraffenland, wherefrom a new roasted Austria, prepared using each person’s own recipe, would come flying into each person’s mouth. All tongues praised it. All tongues promoted it. And all tongues relied upon it.

When an enthusiasm is no longer so sophisticated, then it becomes louder; then the tongue patriotism becomes the lung patriotism. When our man sang as softly as possible: “What summertime, what wintertime! Just do it once at the right time!” —it echoed back in the liveliest manner: Quibblers, grousers, ignoramuses or cowards. Then we had honest lung patriots (or lumpen patriots?), who thought, Mother Austria would surely lose a few pounds if they didn’t convince her every day how strong she is in the war; but there were still more, too. Among these the most visible were the embargo and boom lung patriots.

One shouldn’t say much about the embargo patriots. The embargos are a national necessity throughout Europe and embargo patriotism is a response to that. Its chief feature is suffering over a disadvantage — it is a sad form of patriotism. The boom lung patriotism has more to do with the war economy. Its law is: if the profits decline, patriotism must rise; whereby it corroborates its selflessness. If, for example, the farmers believe that their business is not as good as it was last month, so they maintain that there is no occupation as ready to be a patriotic victim as agriculture, wherefore they should continue to be rewarded out of thanks. The hops dealers do the same, and the umbrella manufacturers. No profession wants to mean less for the whole than any other; there is a milk patriotism, an egg patriotism, an ox patriotism, a leather, a grain, a spiritual, and many, many other kinds of patriotism […].

There can be found—one must not exaggerate —among the boom patriots, many honest, docile people, who only conduct their business so that someone else doesn’t do it; those are the Get-it-underway patriots. The Get-it-underway patriot would make a good second in any patriotic race, but as a first he wouldn’t run for any price; he is paralyzed by the fear that the others wouldn’t be able to follow him. Whenever there is an injunction in Austria, a ban, an incitement, a financial imposition, which demands a victim, everyone thinks: I would certainly gladly do what is requested, but, see, the others are not doing it and I don’t want to be the dummy. And so many others would so gladly be good patriots if only they knew that the others also are. No person in Austria would have so much success as one who, armed with the necessary power and resolve, would do what is simple and unimpressive and not ingenious and not distinguished: lead them straight ahead.

Alas, until that happens, there are many kinds of patriotism. There are the raucous patriots, who once said exactly what was to be done, and now say “nothing at all anymore,” and then those quieter ones from whom one hardly hears a thing, probably because they sit so high up. Then there are the patriotic festivities and the patriotic infirmities, of which the worst are war painters, war poets and war reporters, then there is the whole war benefaction and war stupefaction and always something else again.

If a singer takes the stage, she does it for a patriotic purpose and is applauded.

If a poet has a poem published, he does it for a patriotic purpose and is acclaimed.

If a functionary founds a club, he does if for a patriotic purpose and is appreciated by the higher ups.

If a lady gives a lunch, so then for patriotic purpose and it is talked about in the newspaper.

If a leather manufacturer founds a prosthesis association, he does it for patriotic purposes and sells his leather.

If a bandage merchant donates to a hospital, he does it for patriotic purposes—like everyone else.

If a beer brewer makes a present of herring, he nourishes the people and sells his beverages.

There are only heroes and patriots these days; whoever is not a hero is a patriot. Everything that was before still exists and seems only to have become stronger through the heat of the war; virtue and sin, weakness and outrage, ridiculousness and greatness.

The battle between them still has to be slugged out.

There is certainly more true patriotism than false, and even of the false patriots some may be genuine. Patriotism is genuine today, but it is also a fashion. And even this adds up to, handled correctly, a positive and a negative, because so many lethargic, passive, calloused people, who otherwise one could not move for anything, have become moldable. The war has melted and softened their hearts, and stimulated their beating, has expanded and distorted and warped and deformed them and made them weak for the good as well as for the bad and put them into an uncertain condition of “I would like to”. From out of this they will grow cold again and grow rigid and remain in whatever form they are currently found.

Who excavates the form?

Who refines the cast iron?

Who casts: “I would like”;

Into: “I must”—?

The Holidays

Instead of Christmas tree candles, flares. Instead of cotton flakes on a trimmed little tree, three meters of snow beneath which the green branches barely poke. If you want to pour iron and ask a question of fate, just go out in front where, in the dark by the sentinels, a rifle volley sputters, then and there. Instead of choirs of angels, from time to time, a grenade whistles, singing through the air. This is how the trenches celebrate Christmas and the turning of the year.

For the first time during the holidays the angel of peace was on earth again; hastily and unsure. Its radiance lit up suddenly in a word from the emperor, then it faded again in front of the gaping mob which sprang up in the enemy papers. No one knows if it will come again. So, the trenches lie dark across from each other. Much less hostile than the newspapers and the ministers of our enemies, mired in their blood guilt.

We wait and know that we will do our duty, if it must go on. It is not up to us whether or not the spring snow will be colored red too. We defend, they attack, our consciences tell us that the same way they did two and a half years ago, but that helps them not a wit. We have offered them the possibility of an end before further victims fall. We have invited them to sit at the table with us, to put the quarrel over guilt or not guilt about the past — even though our consciences are clear — aside, to think about the future. This is the situation. It is now the time of year when those shepherds, who are otherwise called or not called, tend to nourish a little elevating reflection on the peace of the holiday times. But did one even know what peace is? Was that peace: Morocco Crisis, Algeciras Conference, Annexation Crisis, Irredentism, Obstruction, Isolationism? It was a lazy, dark, churlish, pale peace, a ghost of a peace. In war, all of Europe has come to know peace. Peace is: doing during the day and sleeping at night, and not the other way around. Peace is: to lie in a bed and not in a clay ditch. Is: if it rains to let yourself be protected by a house and not to be standing outside in the rain to protect the house. Is: not to have to jump when someone else is taking care of it; not to eat rolls only in memory; not to embrace women only in dreams; not to know dancing, woman, child, café, train, theater only as a far-off, cloudy-rosy swampy fairy tale, from the time when one once — as only the oldest people in the company can remember — on holiday. May the devil take our enemies and we will help him to them, if they risk it, but all of Europe was never as united as in this one point: imagining how it would be if we had peace. If Pane Prokrovsji has his mouth so full, if Monsieur Briand stuffs his mouth even fuller, if Mister Lloyd-George behaves as if he were well fed, they all act as if they did not know that on the trenches rationality sprouted up a long time ago to such a height that the fairy tale could no longer work, and that — even if one is determined to keep on fighting if it must be — one has begun to learn that peace is: not to impose upon the will and the right of another person, when it is not absolutely necessary. We never fought for anything else, but they fought for “punishment” for “barbarism,” for the extinction of “Militarism,” for the honor of “culture,” and such like. And if that was only sanctimoniousness on the part of the leaders, for their people the idea was really eerily genuine, to teach us heretics, who thought differently than they did, with violence and to have to quarter us ad majorem dei gloriam. This will be the greatest human lesson of this war, which will probably not be forgotten either a generation later.

God will probably protect Europe from a thirty-year’s war, but in respect to the impatience from which it sprang, this war already seemed like it is just at its start. While in those days it was religion that served the political ambition of the wagers or war, it was nationalism that swept the people along this time. Nationalism was not the only cause of the war, but its intoxication, its marching, its battle songs, those things that made it into a war of Volk against Volk. The language difference is the high and thick wall through which, from Volk to Volk, only a few pass. The others do not see what is happening on the other side, and if they usually do not immediately imagine the worst, in the moment of excitement they happily tell tales of how on the other side little children are devoured. Man is generally a mistrustful animal, who only trusts another man when he has been forced over a time to eat out of the same bowl as him. But in earlier days, one didn’t trust anyone outside of the relations, the same city or the same little piece of land, while finally one has expanded it to the big states and nations, but no further. To admit this weakness to one’s self is not an argument against a healthy national feeling, which follows the motto: your shirt is closer to you than your jacket, and which rejects a cosmopolitanism that would like to throw its own goods and chattels out the window unbidden, in order to give them to the world. But in the same way in which, after the Thirty Year’s War cut up the world like a fissure into Protestant and Catholic halves, springing over all national borders, one learned all at once how to handle the religious question so that it no longer had anything to do with big politics, thus it is also not out of the question that as the result of this war, the national idea, which before the war had reached its highest tension, could experience a similar alteration.

Christmas-time-world-peace-music? We have tasks that for now lie closer at hand. But as long as we have a moment for once, perhaps everyone would like to consider the past and future a little. What existed on a large scale in Europe, we had in our own house in miniature. The war taught us with two gigantic examples how to distinguish between nationalism stemming from hate, arrogance and not wanting to understand the needs of others, and a national feeling which very carefully ascertains how far it can accommodate the other, while still fighting to the utmost for its fundamentally acknowledged rights. When, then, the crippled, old, shot-up earth comes to hobble for the first time through a peace-spring-sunshine, perhaps we will have forgotten that it was under the sign of the second form of nationalism that no one bled as much, or was as victorious as we Austrians.

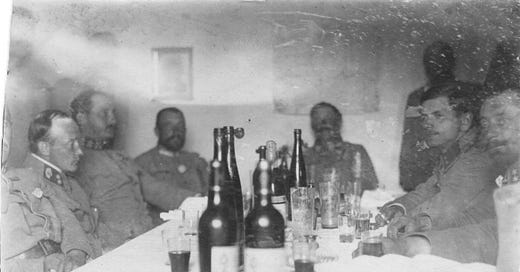

Musil, on the left, with his comrades on the Italian front in 1915.