The fateful year, 1938, began with petty tensions between the Musils and the Fürsts, exacerbated by Blei’s machinations. Apparently Erna had called Martha a “hellion” and complained to Blei that she made things excessively difficult; she complicated communication with patrons; she made fusses about food; she limited Musil’s communication with others (“Robert, you’re too tired now for such questions”).[i] Erna was not the only one who experienced Martha as an uncongenial wall separating her from Robert. Martha wrote to Arnim Kesser that Blei was “jealous, because he did not succeed in driving Robert away from her. Blei behaved badly –spiritually—toward almost everyone; and when he attempted this toward the end of our relationship with Robert, it ended”[ii]. But the Musils did manage to make up with the Fürsts, who had, afterall, done an enormous amount for them. At a dinner at the Askonas ,Musil confronted Erna in an adjoining room about having insulted Martha, and she minimized it, saying “hellion” was just a “schoolgirl expression” that she casually used with lots of people. The break was plastered over, but never fully healed. [iii]

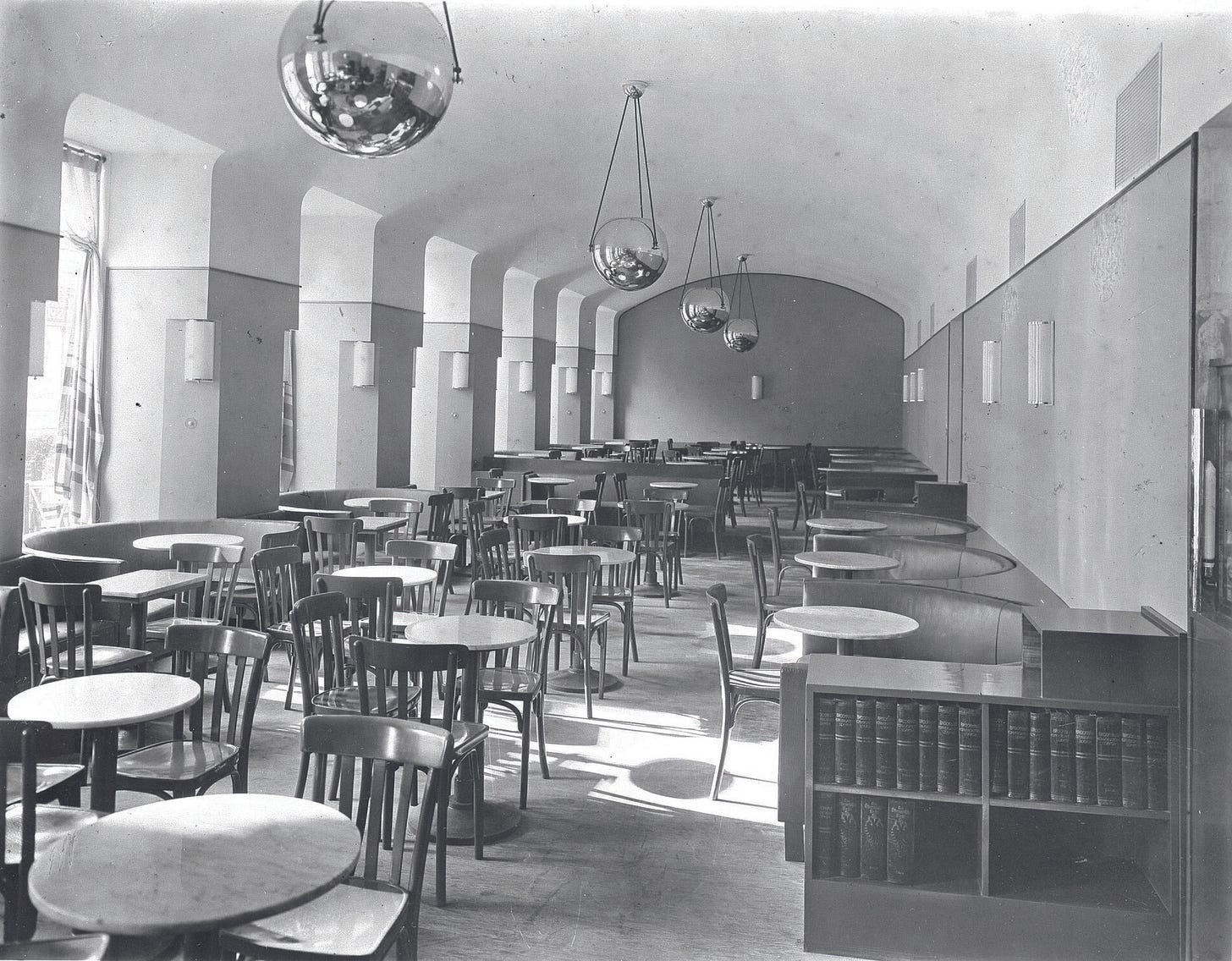

Other relationships may have also been suffering—under the pressure to finish the novel, now scheduled to be out in the spring. To Allesch, he wrote that he was forced to “wear a sack” over his head, and was in no condition to “fulfil his duties to friends or mankind.”[iv] Soon, most of the friends whom Musil was neglecting would be scattered across the globe, all attempting to survive with varying amounts of resources. At the end of February Musil meet up with Soma Morgenstern, Josef Roth and the Hebrew poet, Abraham Sonne (Avraham Ben Yitzhak), at Café Museum. Morgenstern, afraid that Roth would be very drunk and insult the easily offended Musil, had brought Sonne along as a calming influence and mediator. Roth was in Vienna in the adventurous capacity as representative of Otto von Habsburg, who wanted to come back to Austria to save it from Hitler ! They spoke for two hours, almost exclusively about politics. Roth and Musil were still optimistic about the protective hand of England—Musil did not believe that Chamberlain would allow Hitler to take over Austria, but Sonne and Morgenstern “were already so certain that Austria was lost, that” they “had decided in Janaury 1938 to leave Vienna.” But neither of them managed to flee in time and were in great danger for their lives. Roth returned to Paris, and Musil left Austria five months later.[v]

(Cafe Museum, 1930)

On March 11th, the Austrian Bundeskanzler, Schussnigg, stepped down and on the 13th, Austria was joined in Anschluss with Nazi Germany. Of immediate import to Musil: Gottfried Bermann-Fischer, who had been manager of the publishing house since his father Samuel’s death in 1934, [vi] fled with his family to Rapallo; his publishing house was put under the provisional management of a party operative; no more advances were paid to our struggling author; and, since many of Musil’s Jewish friends fled Austria, the financial and spiritual basis of the Robert Musil Fund was dissolved. On the 14th of March, the day Hitler marched into Vienna, Musil was reading D’annunzio’s A Child of Pleasure. [vii] The next day, the Fürsts went to say goodbye to the Musils and later, explaining that “Frau Musil was made of 90% angst,” remembered that after Hitler’s entry into Austria she wouldn’t leave the house without wearing a swastika on her lapel, thinking it would make people overlook her pronouncedly Jewish appearance.[viii]

By April, Musil had the proofs of twenty chapters ready for publication (the so-called “proof chapters”—the last sections he ever approved for publication, but then withdrew) and was planning to add two more. He had been frustrated by the publisher’s rush, had asked for an extension, and had been angry when Bermann-Fischer advertised that the book would be out by Christmas—so the publication date was put off until Easter. But it seems that Musil, not hearing from his publisher for a while, then blamed the publishers for the hold up, withdrew the chapters, and began yet another revision.[ix]

En Face, p. 272, Corino’s Gespraech with Fuersts [i]

[ii] MMB, 67, qted 273 En Face

[iii] En Face, 272

[iv] B Feb 2, 1938

[v] See En Face, 368-9

[vi] Bermann-Fischer Verlaggegründet 1886 von Samuel Fischer in Berlin. Er verlegte unter anderen Gerhart Hauptmann, Henrik Ibsen, Émile Zola, später Hermann Hesse, Hugo von Hofmannsthal, Thomas Mann, Arthur Schnitzler, G. B. Shaw und Oscar Wilde und hatte großen Einfluss auf das deutsche Geistesleben – auch mit der 1894 als Nachfolgerin der 'Freien Bühne' gegründeten Zeitschrift 'Neue Deutsche Rundschau'. Nach dem Tod S. Fischers 1934 übernahm sein Schwiegersohn Gottfried Bermann Fischer den Verlag. Bereits 1936 musste Bermann Fischer emigrieren. In Berlin wurden Teile des Verlagsgeschäfts unter dem Namen 'S. Fischer Verlag KG' fortgesetzt. Dieser Verlagsteil wurde von Peter Suhrkamp geleitet und war für die politisch 'unbelasteten' Autoren bestimmt. Er trug ab 1942 den Namen 'Suhrkamp Verlag KG'. Den anderen Teil des Verlags mit den kritischen und regimefeindlich eingestellten Schriftstellern transferierte Bermann-Fischer 1936 unter dem Namen 'Bermann-Fischer Verlag' nach Wien. Nach dem 'Anschluß' Österreichs an das Dritte Reich (März 1938) emigrierte G. Bermann-Fischer zuerst in die Schweiz und von dort nach Schweden, wo er erneut Literatur deutscher und österreichischer Autoren publizierte (Berman-Fischer Verlag, Stockholm ab 1938). Nachdem auch in Schweden eine immer deutlichere Pro-Deutschland-Stimmung aufkam, floh die Verlegerfamilie im Juni 1940 in die USA, wo Bermann-Fischer seine verlegerische Tätig(KA Institutionen und Organe)

[vii] Corino, 1929

[viii] [see note, 376 and Bruno Fuerst, Musils Spaete Jahre, in En Face

[ix] To Rosin, he wrote that although th work had been already practically done, because it was to appear at Easter, once it became clear that it would not be published in the near future, he took the opportunity to go back and slowly revise it once more. Although he had been told that the pause in business would be lifted soon, he suspected that the consequences of this new upheaval would—aside from the gain in time—not be favorable for him.

It reads well! It looks as though you have plenty of biographical material to bring his story to life; and historical perspective to make it meaningful. Nice work!