I had a wonderful conversation with Agnes Callard the first reader of my biography book draft last night. She came prepared with a list of questions the book had raised for her, questions for me to possibly answer, but also some that probably must remain unanswerable.

The discussion touched on the question of whether a biographer is responsible for explaining her subject—his or her contradictions, foibles, actions? to what extent? Or, conversely, does the attempt to reduce the irreducible to theories or explanations dangerously delimit one’s subject?

Agnes said that she appreciated that I did not theorize too much, but that this made her sometimes feel at sea. Which, when I thought about it later, probably would have been what Musil would like….for he didn’t like giving readers (or himself) simple scaffolds to hold on to.

Some of her questions:

What was the cause of Musil’s “restlessness,” his tendency to move, like Ulrich in the novel, from one career, woman, perspective to another? What was he looking for?

One answer (which I only thought of after the discussion) might provisionally be that, when it came to careers or disciplines, he saw them as artificially separated, so he was trying to take the best parts from each and combine them. He had to run through each of them to find them dissatisfying and then move on to create his own conscilience in an Art that combined elements of all. But also, in general, I don’t think he was so much restless as metaphoric: he would say that each experience, person, place, while distinct, all contained similar allegorical or metaphoric content: the novel about Ulrich and Agathe could have been told, he claimed, as the story of a Sufi mystic. No matter what he was circling through, he was asking the same set of questions surrounding: how to live the right life in a world that has lost most of its guiding principles, its Archimedean point. And another related question we arrived at towards the end of the discussion: Is it possible to be the sort of person Musil was or was trying to be, the sort of person he was looking for (attempts to find another kind of human being) in this world? Can one resist being polarized, reduced, caught in habits of thought and life?

But even if he wasn’t restless, he was perpetually dissatisfied—which came, in part, from his inimical trait of always looking at different aspects of everything. If something were successful in one way, it was probably a failure in another.

Was Martha the other human being whom he sought? What was it about her that satisfied him?

I think we both agreed that instead of being the Other Human Being Musil sought, Martha became One with him in a way, so she could not be—or could not remain, as they merged—the Other. But why they were so well suited? She was a woman without qualities in a way: open, experimental in moral realms and eroticism, she was an avaricious reader….they talked (Nietzsche said that Marriage is a long conversation, so you had better marry someone you can talk to!) and talked and talked. My generous reader later also asked whether Martha had undergone a change (“the taming of Martha”) over the course of the marriage; she had seemed so fierce and independent as a younger woman, but then she devotes her entire life to the fostering and proliferation of Musil’s work, not her own. What happened? I said that she was still domineering after the marriage, but in his interest (many people complained that she managed him, controlled who got to see him, what he ate, etc.). He did encourage her to do her own art (and she did some, mainly to earn money), but she would claim she was too lazy, not committed. So instead, she became what he called one of the “two authors” of his works, not just because she made it possible for him to survive and keep writing, but because so much of the writing is based on her life experiences. In some ways, their strengths and weaknesses complemented each other. They were two as one against the world.

This was my question, inspired by my reader’s: Musil says over and over that WWI and WWII were caused by our inability to understand our emotions, our urges, our violent capabilities, but he does not ever (as far as I can think of) explain what we might do differently to better manage these emotions. What was his answer to this problem?

My answer to this is just more questions: on the one hand, I think he felt that it was important not to underestimate the power of emotions or the wide spectrum of what he called human plasticity—that we changed radically from one moment to the next, from well-behaved social moralists to raging violent killers in war, for example, or to savage beasts in bed. So an answer would be to know ourselves better, recognize this. Not to repress it, but to incorporate our knowledge of this into our provisional theories about how to live. What confuses the matter (or does it not?) is that he favored the intense moments of life, the passions and even the excitement of war…so he certainly did not want to repress them or dull them. Just somehow educate to undestand them? Education, an aesthetic-ethical education, is, to be sure, his basic reform principle.

A difficult question was about how, as I claim, his scientific studies can still be seen as important in his later work.

One answer is in his chapters on the psychology of feeling, which are largely revisiting his studies in Berlin at University in psychophysics. Which raised the question of why those chapters are there: what did they mean to Musil, what do they mean to the novel? Briefly, they explore the ways in which we know the world, one of the first strands of all philosophy that aims to ask how to live the good life: first we have to know the world, investigate the role of perception, senses, and that of reason (and emotion), before we know how to act. His studies at the University are, I would argue, of a piece with all of his work as a writer: how do we see, from different perspectives, what is the role of subjectivity, what can be reliably known, is Truth only something approximately probable? This also relates to my reader’s question about Ernst Mach: what was so important about him for Musil (and for others)? I think, simply summarized: Mach was a sort of bridge between art and science for Musil because he admitted that even science was based on constructed categories (Denknotwendigkeiten or necessary mental constructs) that were not strictly accurate or reducible. My reader brilliantly sugegsted that Musil took Mach’s premises more seriously than Mach himself, which created a sort of crisis (consider Toerless and his imaginary numbers: how could these irreducible, imaginary things be used to build bridges?). An attempt to understand this and figure out how to live in a world based on such compromises is Musil’s life work. Instead of throwing out science because it is only an approximation of truth, he counselled merging the kinds of knowledge that we glean from Science with that we glean from Art and Essayism, to understand that the realms are not altogether unlike, but can temper and illuminate each other? Like Gödel, he did not see the incompleteness of scientific proof as a cause for despair, but a wonderful opening into infinity. Not being able to definitively prove something did not spell nihilism or despair. The real danger was when people claimed they could come up with final solutions.

Another big question for my reader was whether Musil’s work and life might be considered a Failure. Why did he never complete the book? What was he doing endlessly revising and revising over the last decade or more in exile?

I have answers for this, but now understand that I did not incorporate them enough into the draft. In fact, the preface to my World as Metaphor is called something like Failure as Modernist Success. Basically, Musil’s stance as radical open experimenter did not really allow for coming to conclusions, choosing one ending over another, ceasing inquiry. His Utopia of the Next Step meant that one judged each event only by what it brought in its wake. His utopias are not closed systems, which would be dystopias, but rather ongoing, living non-systems. Further, psychologically he was in a sort of bind. He wanted success and was bitter about his lack of it (popularly, financially), but also condemned popular success in others, as somehow cheap, too easy. After the publication of one of the volumes of The Man Without Qualities he said something like: if this book succeeds it will have been wrong. Further, I think there was a form of neuroses at work: an eternal deflection and digression, avoidance of end, death, consummation. Further, the Totalitarian Terrors encroaching from all sides made a resistance to finality even more important, even if wildly impractical and even self-destructive. So, Musil’s resistance to closure, in life, in politics, in thought, and in art may really be what makes him so great. It is a mark of radical honesty and bravery and an invitation to think and be differently in the world.

Agnes also asked another related question: Why is there so little PLOT in Musil’s work.

While I might not have had an answer to this a few years ago, my time spent with his life has made me think that Musil’s resistance to plot is related to his rejection of cause and effect trajectories. He was explicitly trying not to write narratives based on simple assumptions about causal relationships. He felt that we create fictions (personal narratives, theoretical models, and in novels) based on very limited ideas about why things happen and he was striving to write a novel that did not reduce reality in that way. It is an ethical, a scientific, and an aesthetic issue all at once. But it returns us to the question above: Is it possible to exist in this world as the sort of person Musil was? In other terms: is it possible to have a novel or a life view that does not reduce the world to more simple (even if inaccurate) stories with beginnings and ends?

There were many other very fruitful and exciting questions and gropings towards answering, but I will stop here for now (since my theory is that one can still keep things open even when one contains something inside the pages of a book or a blog post, just as long as one acknowledges that no final conclusion has been made).

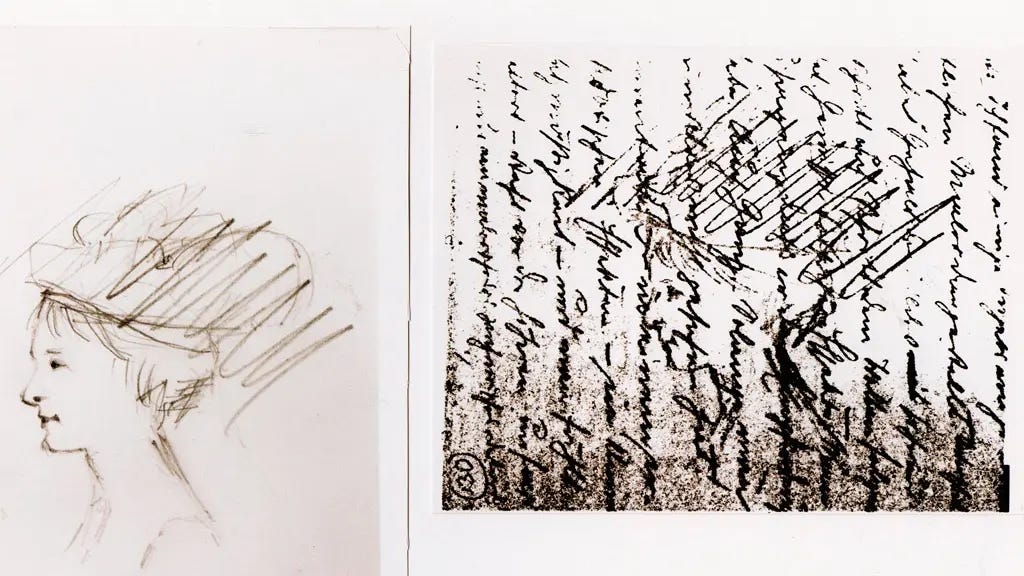

Above, a sketch probably of Herma, rescued from a palimpsest in Musil’s notebooks. Herma, whom we know so little about, is in many ways an object lesson of the unanswerable questions. Was it right to clarify the image which Musil has purposefully written over. Is something both lost and gained?

Not much to add other than that this was a great read! I'm still making my way through the second volume of The Man Without Qualities, but your blog is such a great resource and helps me keep up my motivation in this very rewarding, but often exhausting read