There are many differing descriptions of Musil’s social bearing. Some maintain that he was quiet and foreboding, others that his conversation was effervescent, witty, fascinating and wide-ranging. One catches a sense of the lively Musil in some of his letters to his close friends. He makes jokes, tells stories, is often extremely charming and courtly, overflowing sometimes with thanks but other times with sardonic bitterness. It seemed to depend very much upon the person or persons he was with—whether he trusted them, whether he thought it was or was not worth his while to get involved in debate or disagreement, whether he felt appreciated. A number of people with whom he obviously had a good rapport note that his conversation never relied on set phrases or ideas but rather always seemed to be fresh, each new idea springing organically out of the last and often offering just as many arguments against what he had just said as justifications for it. That he listened very carefully is generally agreed upon—and that he asked many questions in order to get a clearer idea of what someone was describing. Sometimes he would ask permission to write something down as if planning to use it as material later. One description—of Musil as a flirt—is so different from the others that it must be included here in order for us to get a full picture. Valerie Petter-Zeiss remembers an “unfortunately rare, therefore all the more delicious experience”—how “extraordinarily amusing large social gatherings were when Musil, surrounded by ‘beauties’—adoring ladies—would suddenly get in a lively mood and draw the attention to himself. He would pay court to the ladies with delightful gallantry, complimenting them in the most exaggerated way; a mild ironic smile, a gleam in his eye revealing how much he was enjoying himself. Martha, quietly satisfied, laughing softly at the other end of the table.” He was, she concludes, “enchanting,” revealing “almost boyish, irrepressible high spirits”.

While he put great store by cleanliness and proper dress (he and Martha once struck someone off the guest list for a reading because he had come to another occasion in shirt sleeves), they were essentially Bohemians when it came to sexual and intellectual mores. When, for example, Martha’s daughter reported in November of 1924 that her future parents-in-law wanted the engaged couple to wait to get married until they could see to the “bourgeois establishment” of a home, Martha wrote she found the stance of the parents “quite correct and really very nice,” quite reasonable and natural, but: “We’re just different, because we stand, I believe, with only one foot on the earth—and that makes us rather like young people.”

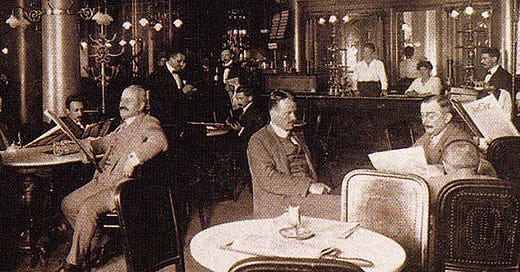

Cafe Central, one of Musil’s main hang-outs in Vienna.

Do you think being Bohemian in sexual and intellectual mores while being conventional in social mores (i.e. - disinviting someone who doesn't dress properly for an occasion) is a reflection of European class traditions, when you compared with his American counterparts?

Ach ja the vanished Kakanien